Network Dealbreakers: When a Network Isn’t Really a Network

By Carri Munn and Circle Generation

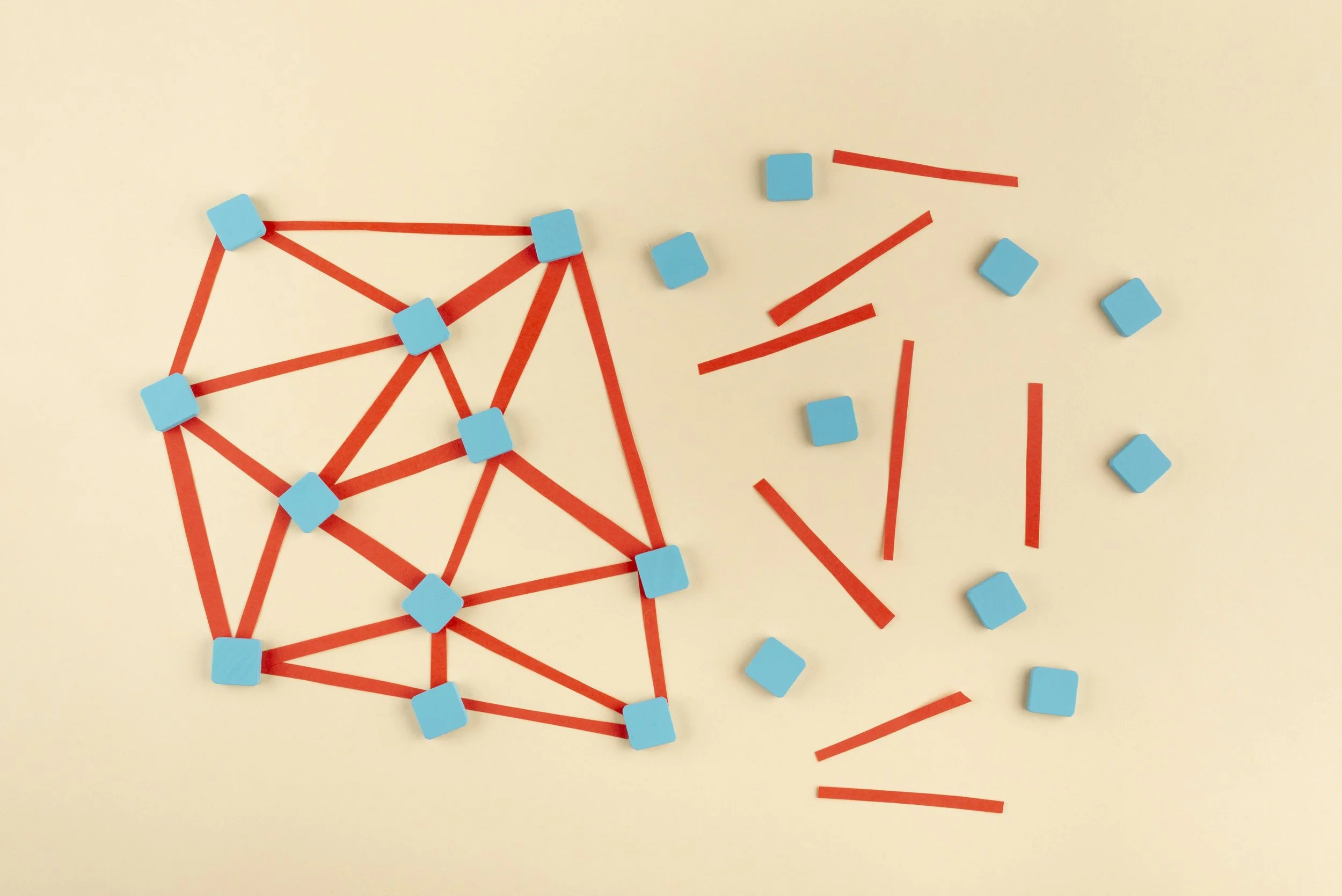

“Network” has become one of the most attractive labels in the social impact world. After more than a decade of increasing calls for collaboration to address global challenges, we’ve witnessed a proliferation of networks in response. The notion of people connected in webs of relationships, collaborating across organisations and sectors, signals promise and innovation. Funders like the sound of it, and participants can feel energised by the potential of this approach. Some organisations even call themselves networks to emphasise their cooperative spirit.

As much as network is a word, it is also a way of describing an approach to collaborating at scale—a means of organising to foster co-creation and collective action. So, what does it actually mean to be a network?

“As much as network is a word, it is also a way of describing an approach to collaborating at scale—a means of organising to foster co-creation and collective action. ”

Healthy networks feel alive with energy, ideas, and contributions from many participants. In these networks, we see a clear, shared purpose and cultures of permission that invite members to come forward to lead initiatives. In struggling networks, we often see structures and assumptions transposed from organisations: centralised authority, planned outcomes, and measurable objectives achieved through prescribed processes.

These traditional organisational approaches are often a mismatch with the network context. For example, when a network operates according to these structures, participant choice and contribution become constrained. Metrics for assessing progress against predetermined goals are not a helpful way of evaluating the current and future value of the emergent outcomes created by a network.

In this article, we highlight how some choices made by network leaders can unintentionally veer in the opposite direction of network principles and practices. We call these Network Dealbreakers. The result can restrict interactions, limit participation, fracture trust, and undermine network health. Network dealbreakers generate patterns of behaviour that crush the potential for collective value creation.

Below are four common dealbreakers with examples of how they’ve manifested in networks we’ve worked with over the past several years. Drawing upon insights from our consulting practice and conversations with practitioners, we share reflections on why these dealbreakers occur, why they don’t work, and options for restoring a relational approach in your network or collaboration.

1) Directives Trump Agency

Example in action: A global network hosted by a large institution viewed the network as a strategy for advancing its objectives through partnership. In exchange for funding, the host organization outlined the majority of the network’s focus and priorities. The network facilitator did not have autonomy to engage members to explore common interests. As a result, new members could not be recruited and the potential for learning, coordination, and collaboration across existing participants was limited.

|

How to spot the pattern: One organisation or small group sets the agenda for the network. Rather than listening for potential at the intersection of common interests and contributions, the small group resists developing shared learning, sidelines initiatives bubbling up among participants, and asserts its sense of direction for the network. |

|

Why it happens: People often default to what they know. In a network context, centralised organisational structures are most familiar and therefore tend to be replicated. Through an organisational lens, engagement and feedback processes may be viewed as time-consuming and inefficient. Discovering pockets of potential at the intersections of shared interest can feel slow to those focused on achieving tangible results quickly. The small group at the centre of the network may believe they know best and fail to check their assumptions with other members. |

Why it doesn’t work in networks:

|

Ideas to restore a relational approach:

|

2) Self-Interest at the Expense of the Whole

Examples in action: A multinational corporation hosting a network prioritised its self-interest by stifling dialogues and initiatives co-created by participants. The topics the host organisation took off the table were the ones that held the most interest for members. This significantly limited the time, energy, and enthusiasm participants devoted to the network. Participants drifted away when they realised the network was not a vehicle to do the work that was significant to them, and the network folded.

Another example arose in a global network focused on equity and agricultural supply chains. A member of a large corporation, seen as crucial to the network’s legitimacy, asserted their agenda to influence network activities and was not accustomed to combining their perspective with others to find common ground. Because the network lead was trying to preserve this member's participation, there wasn’t anyone effectively advocating for less powerful participants. Ultimately, the network did not achieve the desired legitimacy within the agricultural sector due to the lack of authentic inclusion.

|

How to spot the pattern: This dealbreaker arises when goodwill is extracted from relationships to serve some participants’ interests at the expense of others. It can also manifest when network participants are repeatedly engaged in a transactional manner—for example, gathering data without clearly communicating how it will be used or offering anything in return for members’ time and input. |

|

Why it happens: This often stems from a lack of communication about power and impact. Even with good intentions, participants can unknowingly harm each other. Without open, honest conversations about which behaviours support or limit members’ capacity, people may not trust others to collaborate, co-create, or honour commitments to the shared purpose. |

Why it doesn’t work in networks:

|

Ideas to restore a relational approach:

|

3) Shadow Power Over Consent

Example in action: Key stakeholders invited to a city’s climate policy initiative appeared ready to collaborate to achieve climate goals. However, multiple parties circumvented the process by engaging political leaders through back channels. When community members realised the negotiations in meetings differed from the side conversations, they lost trust and withdrew. Collaboration was perceived as performative rather than authentic, and decisions were not made publicly based on stakeholder consent.

|

How to spot the pattern: Shadow power occurs when power—who has it and how it is exercised—is not visible or equitable. It manifests when coordinators are not transparent about decision-making or participant involvement. Choices made without consent can skew decisions, and failure to listen to segments of the network exacerbates inequities. |

|

Why it happens: Time pressure, lack of trust, fear of losing influential members, or limited coordination capacity can all lead to this dealbreaker. Facilitators may prioritise engagement from members with positional power rather than the network as a whole. Avoiding difficult conversations is often easier than facilitating them. |

Why it doesn’t work in networks:

|

Ideas to restore a relational approach:

|

4) Programmes Not Contribution

Example in action: An international network focused on innovation invested heavily in member services, which meant staff led many deliverables. At convenings, most time was devoted to staff-led initiatives rather than participant contributions. Maintaining programme work created a fundraising burden, and staff felt pressure to prove the value of the programmes. Without sufficient engagement, opportunities to leverage knowledge, creativity, and contributions from the network were missed, perpetuating a transactional culture and staff burnout.

|

How to spot the pattern: This dealbreaker appears when paid staff deliver the work of the network instead of supporting participant-led activities. Networks may focus on deliverables rather than relationships, learning, or emergent collaborations. |

|

Why it happens: Funders tend to fund programmes, creating pressure to deliver on expectations. Coordinators may also view value transactionally, fearing members will only benefit if given tangible “things” from a list they can quickly grasp. This can lead coordinators to shoulder most of the work, while participants expect to receive rather than co-create value. |

Why it doesn’t work in networks:

|

Ideas to restore a relational approach:

|

Bringing It Together: Strengthening Network Health

Network dealbreakers aren’t just operational issues—they signal underlying dynamics of trust, culture, and power. Left unaddressed, they can turn a vibrant network into a ghost town. By spotting the patterns that give rise to these dealbreakers and engaging them with awareness and care, leaders can transform them into turning points that deepen connection, re-orient participants to the shared purpose, and reinvigorate network health.

Through examining these four common dealbreakers, we see how challenges arise, the patterns that underlie them, and ways to restore a relational approach—one that supports collaboration, participation, and collective value creation. Healthy networks recognise that every participant has dignity, agency, and unique ways of engaging and making sense of the world.

The challenge—and opportunity—is to create conditions that balance individual and collective needs in real time. Networks reflect the broader power dynamics of their ecosystems, reminding us to avoid approaches rooted solely in organisational structures that can become dealbreakers. By observing patterns of interaction and focusing on aliveness, leaders can engage strategically to support the dynamic balance between structure and emergence, fostering creativity, collaboration, and collective well-being.